-

Articles

The Future of Renewable Energy Corporate PPAs in Thailand

On 10 December 2024, Intersect Power LLC announced a strategic partnership with Google and TPG Rise Climate, with the aim of providing scaled renewable power and storage solutions to new data centers, designed to deliver gigawatts of new data center capacity across the U.S. Google hopes to replicate this model in multiple markets across the U.S. and around the world; this article examines how the model might work in Thailand.

Thailand’s renewable energy industry

Thailand’s utility-scale renewable energy sector went live in 2007, when state-owned electricity utilities offered to buy electricity from private renewable energy producers pursuant to power purchase agreements (“PPAs”) in which an “adder rate” was paid on top of the prevailing wholesale electricity price (since that time, “adder rates” have been replaced by feed-in tariffs).

At that time, the Utilities, the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (“EGAT”), the Provincial Electricity Authority of Thailand (“PEA”), and the Metropolitan Electricity Authority (“MEA”), held a legal monopoly on the transmission and distribution of electricity, and the private sector was prohibited from selling electricity directly to end users: the private sector could sell electricity only to the Utilities, who then sold it to end users.

As of September 2024, renewable energy accounted for 10% of Thailand’s generated electricity; in the short term, the installed capacity of renewable energy generation is likely to increase by an additional 6.98 GW, as a result of the most recent round of renewable energy PPAs issued by the Utilities.

Thai law does not yet obligate businesses to report greenhouse gas emissions embedded in their operations or to use electricity from renewable sources, but many companies in Thailand are faced with pressure to reduce carbon emissions due to laws in other jurisdictions, and the use of renewable energy is an important method of achieving these reductions.

The transitional phases of the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (“CBAM”) require EU importers of cement and steel from Thailand to report both direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) embedded in their imports, although there is no need to buy and surrender certificates. Apparently, European importers already are asking Thai manufacturers in many sectors to report greenhouse gas emissions, using a scorecard approach in which businesses with a lower carbon footprint may be preferred over suppliers with higher footprints. Therefore, it is not only data centers that want the option to acquire renewable electricity.

Corporate PPAs in the energy market

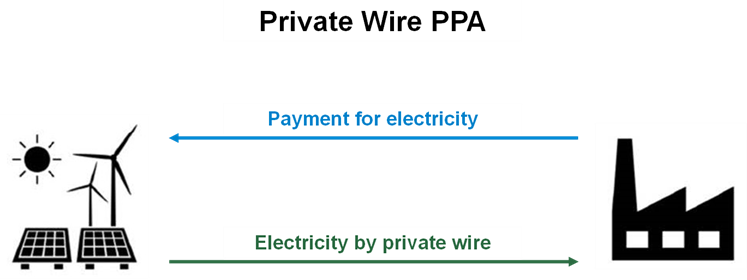

The Utilities’ monopoly on selling electricity to end users came to an end on 10 December 2007, with the introduction of the Energy Industry Act. Solar rooftop developers have taken advantage of the liberalized market by installing solar panels on factory rooftops and selling electricity directly to the corporate end-user pursuant to a PPA (“Corporate PPA”). Most rooftop Corporate PPA end users occupy the building on which the solar panels have been installed; these installations often are referred to as On-site PPAs, Co-located PPAs, or Direct-Wire PPAs.

On-site PPAs have existed in Thailand for more than a decade, and while they will continue to play an important role in future PPAs when the generating facility is located on the premises of the end user, they will not be useful for end users that lack sufficient space for a solar rooftop, wind farm, or other renewable energy facility.

Some private energy producers have established electricity generating facilities within industrial estates in Thailand, enabling factories and other end-users in those industrial estates to acquire electricity directly from the producer, via a distribution network in the industrial estate, but to date many of these facilities are based on electricity generated by thermal energy (such as natural gas) rather than renewables. This is largely due to the fact that more land area is required to generate a given amount of electricity using wind or solar sources than using thermal power plants.

The bankability of an energy project underpinned by a Corporate PPA is largely dependent on the creditworthiness of the corporate offtaker: unlike State-owned Utilities, a corporate offtaker often cannot rely on financial support from the government, and the offtaker’s insolvency can be disastrous for the financial viability of the project, unless the assets of the insolvent offtaker are acquired by a new company that continues to buy electricity pursuant to the Corporate PPA. For this reason, large, established companies with strong financial track records will find it easier to procure a Corporate PPA than new, thinly-capitalized companies with no significant track record.

Implementing the Google model in Thailand

Google’s recently-announced renewable energy procurement model aims to co-locate its data centers with renewable energy power plants, in industrial parks; this part of the model is possible under Thailand’s existing Energy Industry Act. The more challenging aspect of the model is Google’s desire for the renewable energy plants to be grid-connected. The primary limitation of solar energy is that it only generates electricity when the sun is shining, and wind generates power only when it blows, with the result that the electricity output of wind and solar plants is high at some times and low at others. For a data center to rely on wind and solar power for 100% of its electricity consumption, the installed capacity of the relevant wind and solar farms needs to be larger than the data center’s planned consumption, and economically it makes sense to sell the surplus generated by that excess capacity to other users.

The sale of the surplus is where hurdles arise in Thailand’s current regulatory landscape. One solution is to sell the surplus electricity to Utilities (for subsequent sale to end users), but presently there is no framework that requires Utilities to purchase surplus electricity from the private sector. The private generator would need to enter into a PPA with the Utility for the sale of the surplus electricity, and bidding rounds to apply for a PPA with Utilities occur only infrequently.

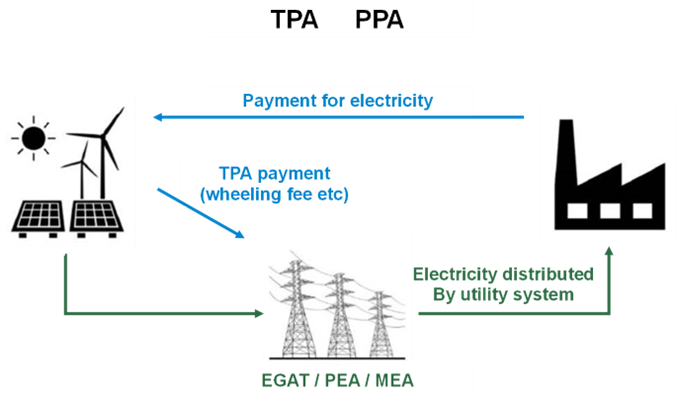

Another approach is to sell the surplus electricity directly to end users outside the industrial park pursuant to separate Corporate PPAs. As these additional offtakers are not co-located with the electricity facility, it is necessary to use the grid owned by the Utilities to distribute the electricity.

Strictly speaking, this is provided for in the Energy Industry Act; however, its implementation is not as widespread as Co-located Corporate PPAs, and the Utilities may not consider widespread third-party access to their infrastructure to be in the Utilities’ own best interests.

Corporate PPAs are great for end users, less great for Utilities

Private renewable energy producers already are in competition with the Utilities. They sell a product the Utilities currently don’t offer, and they have a cost advantage.

The price payable per kWh of electricity for an On-site PPA in Thailand is often less than the tariff charged by Utilities, made possible by year-on-year reductions in the levelized cost of electricity (“LCOE”) from solar energy. The financial benefit to the end-user comes at a cost to the Utilities, in the form of reduced demand for electricity generated or sold by the Utilities. Thailand’s wind farms are predominantly onshore, and the LCOE of inshore wind production is on par with that of solar. The private sector writing solar Corporate PPAs (and, in the future, wind as well) in effect is in competition with the Utilities, as the private sector can sell electricity more cheaply than the Utilities, and has a ten-year head start on the Utilities in terms of selling renewable electricity.

Utilities have purchased electricity under renewable PPAs for years; however, until recently, renewable energy certificates (“REC”) for the projects were held by the project owners, not the Utilities. To date, Utilities have not offered renewable electricity as a differentiated product, although that is set to change. Under the big lot feed-in tariff (“FiT”) PPA round of 5.2 GW covering the period from 2022 to 2030 and the follow-on 2.1 GW round, the Utilities and/or the Thai government will retain the RECs for renewable energy production under their FiT schemes.

The Utilities plan to sell renewable electricity to end users under a new utility green tariff, which currently is being developed to enable Utilities to sell the electricity they acquire pursuant to renewable energy PPAs at a higher price than electricity from non-renewable sources. Therefore, any sale of renewable electricity by the private sector at a lower price than electricity from non-renewable sources will compete directly with electricity sold by the Utilities under their new utility green tariff.

Third Party Access required of licensees since 2009

The Energy Industry Act opened the door to Off-site Corporate PPAs by requiring any licensee who owns an Energy Network System to allow other Energy Industry licensees to connect to the Energy Network System in accordance with terms established and announced by the owner of the Energy Network System (“Third Party Access”).

Energy Network Systems include electricity transmission systems and electricity distribution systems, with the result that all licensees are obligated to provide access to their transmission systems and distribution systems without waiting for guidance from the Energy Regulatory Commission of Thailand (“ERC”) (although to the extent the ERC announces any terms governing for Third Party Access, licensees are required to incorporate those terms into their Third Party Access terms).

Currently, the Energy Industry Act gives energy industry participants the right to request interconnection with the transmission system and distribution system owned by a licensee. If the licensee refuses to allow interconnection, the Energy Industry Act provides the person making the request with the right to apply to the ERC for consideration, and requires the parties to abide by the ERC’s decision.

However, the Utilities have not been quick to implement Third Party Access terms, and currently there is a lack of clarity as to which Utilities are licensees and which Utilities are licensed to operate transmission systems and distribution systems.

The Energy Industry Act required the ERC to issue licenses for energy industry operations to EGAT, MEA, and PEA, and for those licenses to be based on the scope of services provided, and to the rights relating to the provision of electricity within the responsibilities of the EGAT, MEA, PEA as they existed on the date Energy Industry Act came into force.

However, the MEA (which is responsible for the distribution of electricity to end users in greater Bangkok) does not appear on the ERC website’s list of licensees, and the PEA (which is responsible for the distribution of electricity to end users in the rest of Thailand) is listed as holding electricity generation system licenses, but not licenses for the distribution of electricity. If MEA is not yet a licensee under the Energy Industry Act, it cannot be compelled to provide Third Party Access to its distribution network, and until the PEA has a network license for the distribution of electricity, questions can be raised as to whether the Energy Industry Act obligates PEA to provide Third Party Access to its distribution network.

EGAT is listed as having both electricity transmission system licences and electricity generation system licenses, so a Third Party Access request can be made to EGAT; however, the number of end users connected to EGAT’s transmission system is very low, compared with the number of end users connected to the distribution systems of PEA and MEA. Third Party Access to the distribution networks of PEA and MEA would be required to provide most end users with the ability to acquire renewable energy under Corporate PPAs with the private sector, so the current Third Party Access rights would be of most use to offtakers connected to EGAT’s transmission system.

Even if EGAT grants a Third Party Access request, EGAT currently is able to set access costs as it sees fit, provided the fees do not disadvantage energy consumers and the public, and do not discriminate against or hinder energy industry participants. The ERC issued framework guidelines for Third Party Access in 2022, but the guidelines do not yet place a hard ceiling on Third Party Access fees that the Utilities can charge. Instead, they require the Utilities to prepare draft codes for Third Party Access. There were hopes that the Third Party Access codes would be finalized by the end of 2024; however, it now seems more likely that this will occur in 2025, or later, and it is possible that the Third Party Access codes initially will be limited to sandbox and pilot projects, rather than opening up the entire grid to all interested power producers.

While some power producers may be content to wait for the Utilities to publish their Third Party Access codes, other power producers will see the current situation as an opportunity to apply for Third Party Access on the terms that currently apply under the Electricity Industry Act, before the imposition of additional restrictions by the ERC.

Chris has been based in Thailand since 2001 and has more than two decades of experience working alongside Thai lawyers on cross-border M&A and regulatory matters, providing international-level solutions to companies entering the Thai market. His clients include global companies investing or acquiring assets in Thailand and Thai companies engaging in cross-border transactions. He advises international and Thai companies on the development, sale, and acquisition of renewable energy projects in Thailand and across Asia.

His M&A practice has included private M&A, advising institutional and activist investors on SEC/SET reporting requirements and acquisition thresholds, and strategic shareholders on synergistic de-layering of listed group structures. His sector expertise for M&A includes manufacturing, TMT, logistics, renewable energy projects, and the service sector for both buy-side and sell-side, share and asset sale transaction structures. He has advised overseas law firms on the acquisition of Thai law firms.

With a focus on renewables (including transition), Chris’ energy practice has more than 1 GW’s experience in onshore wind, solar (PV, thermal, ground mount utility scale, and C&I rooftop), and waste-to-energy projects. His experience has a broad reach, from due diligence of early-stage projects, advising on EPC/O&M, corporate PPAs, equity funding, and project finance, to pre- and post-commissioning exits and acquisitions.